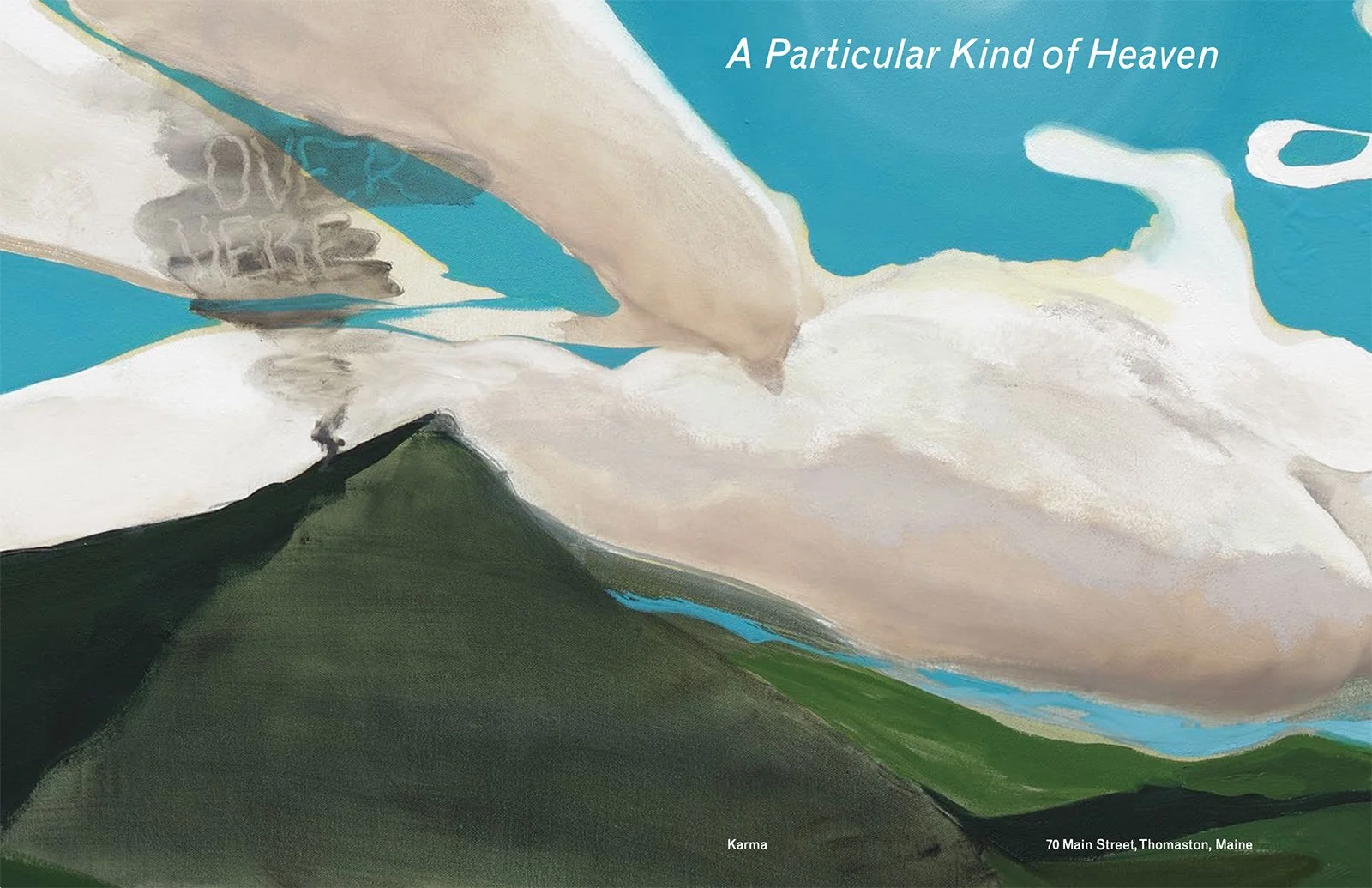

A Particular Kind of Heaven (2024)

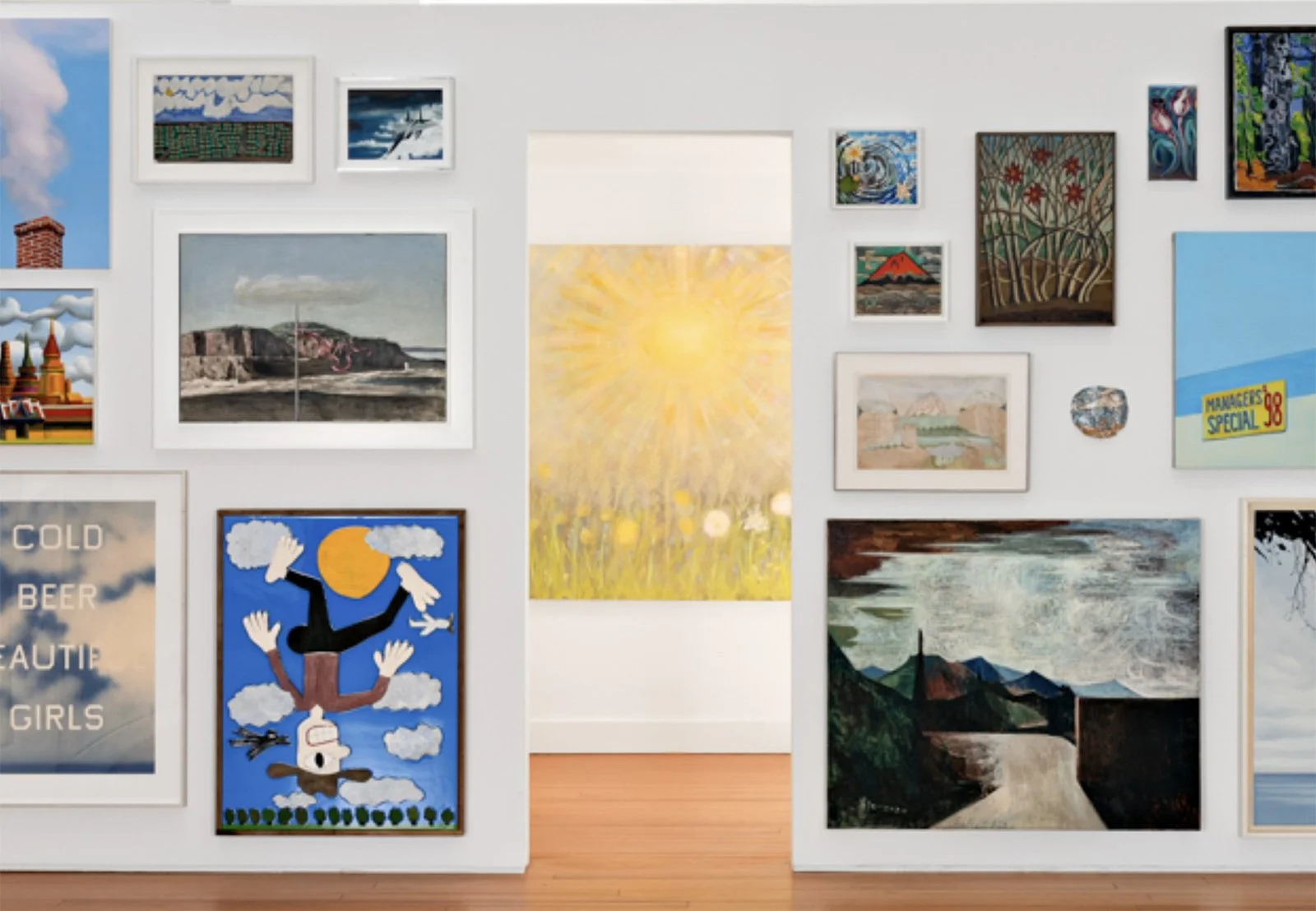

Karma presents A Particular Kind of Heaven, an exhibition of nearly one-hundred-and-twenty works spanning multiple disciplines by over seventy artists, on view at 70 Main Street, Thomaston, Maine, July 21 through September 1, 2024.

A Particular Kind of Heaven presents a wide array of empyrean imagery by a multigenerational group of artists. Sited in a deconsecrated Catholic church, the exhibition probes connections between the spiritual and the natural, the everyday and the sublime. While the near-universal motif of the sky unites the expansive contributions on view, the representation of this subject morphs and multiplies to span pictorial fealty, surrealist interpretation, lyrical rumination, narrative landscapes, geometric and gestural abstractions, three-dimensional works made of sweetgrass and post-consumer paper, and more. A Particular Kind of Heaven is titled after a 1983 Ed Ruscha text painting that calls attention to the idiosyncratic nature of our visions of the sublime and our projections about and on to the American landscape. The exhibition proceeds from dawn to dusk, following the transformation of the sky over the course of a day.

DAWN

The rising sun casts a hazy yellow glow through a veil of clouds in Yvonne Jacquette’s Grey Sky / Barn Side (1969), painted from observation at the artist’s summer home in Searsmont, Maine. The artist attends to her prosaic subjects—carefully-laid wooden boards, leaves stretching skyward, dawn—with a care that inches beyond realism and into the poetic. The foreglow of a sun not-quite-risen comes through in Jacquette’s subtly golden blues. Dawn is also the temporal setting of Norman Zammitt’s THEOGREY.4 (1988), in which the artist fractures light into horizontal stripes that thicken incrementally as they transition from black to periwinkle to simulate the diffusion of light through the smoggy skies of Los Angeles. Leonora Carrington described dawn as “the time when nothing breathes, the hour of silence.” For a moment, all is still.

MIDDAY

The sun is climbing, and the air is beginning to heat up. Maureen Gallace revisits the landscapes of New England time and time again, here distilling clouded sky, horizon, ocean, sand, rock, into a scene of gesture and muted color. In contrast to her intimate canvas, Nathaniel Oliver’s monumental oil painting Over Here (2024) is a panoramic perspective on a mountainous landscape anchored by a lake whose contours pull the eye from the foreground up and through the horizon. A smoke signal suggests the presence of a figure who needs saving; we can use the remaining daylight to find them. Barkley L. Hendricks took breaks from painting his iconic figurative works each winter from 1983 until the early 2000s, escaping the dreary cold of New London, Connecticut, for the warmth and light of Jamaica, a pilgrimage he described as “following the sun to the Caribbean.” There, he worked en plein air to capture the island’s natural beauty, often finishing his small paintings in a single day. Hendricks’s Calabash Bay (Waterview), Jamaica, W.I. (1997), from his series of gold-framed landscape tondos, is a porthole to a world of sky and saltwater bisected almost symmetrically by an expansive horizon. The religious connotations of its form—tondos first became popular in fifteenth-century Italy as settings for Biblical scenes—honor the spiritual impact Jamaica had on Hendricks.

DUSK

As the day winds down, the clouds take on an apricot tinge in Dike Blair’s Untitled (2023), a gouache, pencil, and chalk rendering of an early evening sky. The chalk’s carefully smudged edges mimic the misty veils of color that change by the second during this transformative hour. Like all of Blair’s tableaux, which are based on the artist’s diaristic point-and-shoot photographs, Untitled is but a fleeting glimpse of the world’s banal sublimity. A new body of sky paintings by Blair inspired the theme of A Particular Kind of Heaven. Karma’s New York location will open an exhibition of these gouache works this fall. The orange glow in Seth Becker’s small oil Outrunning a Storm (2024) is even more transient. In thickly-applied daubs, he depicts a roiling tempest as it overtakes a majestic sunset, threatening a moment of peace as a kangaroo dashes ahead of the storm. As Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Maine’s most famous poet, wrote: “Into each life some rain must fall / Some days must be dark and dreary.”

NIGHT

When evening sets in, even the brightest of summer days evaporate. Matthew Wong’s August Sky (2016) braids darkness and light; thick strokes of swirling, wet-on-wet acrylic evoke a terrifying, unpredictable nature that overpowers the human subject. The last vestiges of day reflect on a river traversed by a lone boatman, transforming into hallucinatory orange and purple shards. Alex Katz’s Study for Ocean 10 (2022) captures the light of the moon absent its source as it dances on the surface of the sea; the artist’s gestural white-on-black brushstrokes convey the water’s movement, weight, and transparency. Finally, Gertrude Abercrombie’s Landscape with Church (1939) sets the viewer at a distance, gazing down onto a road that leads to a white church suspiciously similar to the one in which the exhibition is set. A full moon glows auspiciously in the distance. In A Particular Kind of Heaven, the sky reaches beyond landscape and into pure abstraction, into the better-than-real texture of realism, into sculpture, into bending arcs of heavenly light refracting off of and changing the plane of the visible.

Gertrude Abercrombie, Henni Alftan, March Avery, Milton Avery, Seth Becker, Dike Blair, Louise Bourgeois, Katherine Bradford, Joe Bradley, Peter Bradley, Tom Burckhardt, David Byrd, Sean Cavanaugh, Mathew Cerletty, Andrew Cranston, Ann Craven, Verne Dawson, Rafael Delacruz, Nancy Diamond, Jane Dickson, Lois Dodd, Lynne Drexler, Matthew Tully Dugan, Inka Essenhigh, Melanie Essex, Hadi Falapishi, Marley Freeman, Jeremy Frey, Magdalena Suarez Frimkess, Will Gabaldón, Maureen Gallace, Sanaa Gateja, Robert Gober, Barkley L. Hendricks, Nathanaëlle Herbelin, Reggie Burrows Hodges, Ulala Imai, Yvonne Jacquette, Tamo Jugeli, Alex Katz, Zenzaburo Kojima, Hughie Lee-Smith, Jacob Littlejohn, Amadeo Luciano Lorenzato, Kathryn Lynch, Calvin Marcus, Keith Mayerson, Richard Mayhew, Donald Moffett, Yu Nishimura, Nathaniel Oliver, Woody De Othello, Nicolas Party, Francis Picabia, Walter Price, James Prosek, Alice Rahon, Ugo Rondinone, Ed Ruscha, Maja Ruznic, Salvo, Trevor Shimizu, Marian Spore Bush, Hirosuke Tasaki, Mungo Thomson, Anh Trần, Tabboo!, Carole Vanderlinden, Nicole Wittenberg, Jonas Wood, Matthew Wong, Randy Wray, Xiao Jiang, Leon Xu, Manoucher Yektai, Joseph Yoakum, Albert York, Norman Zammitt, and Luigi Zuccheri

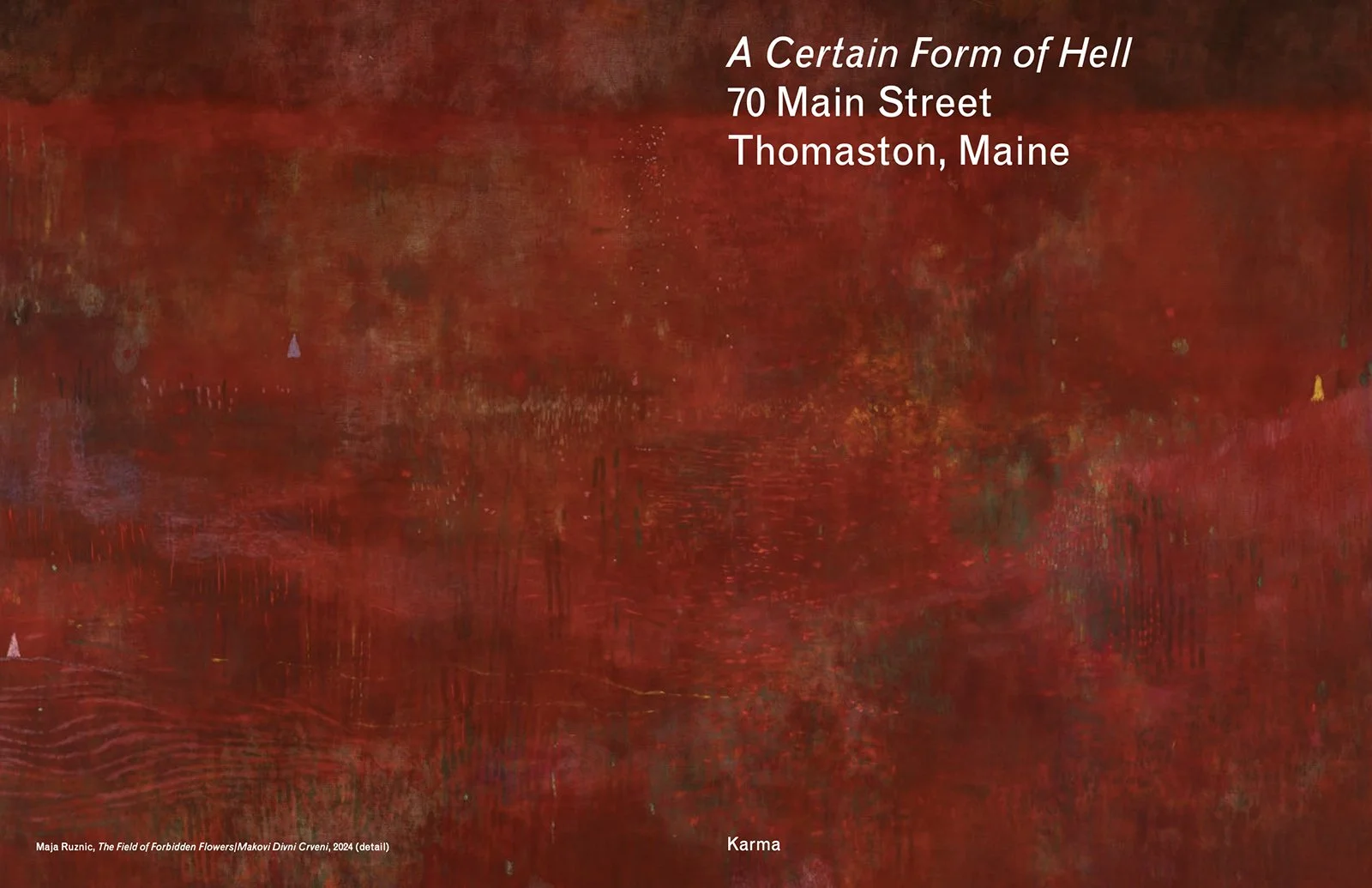

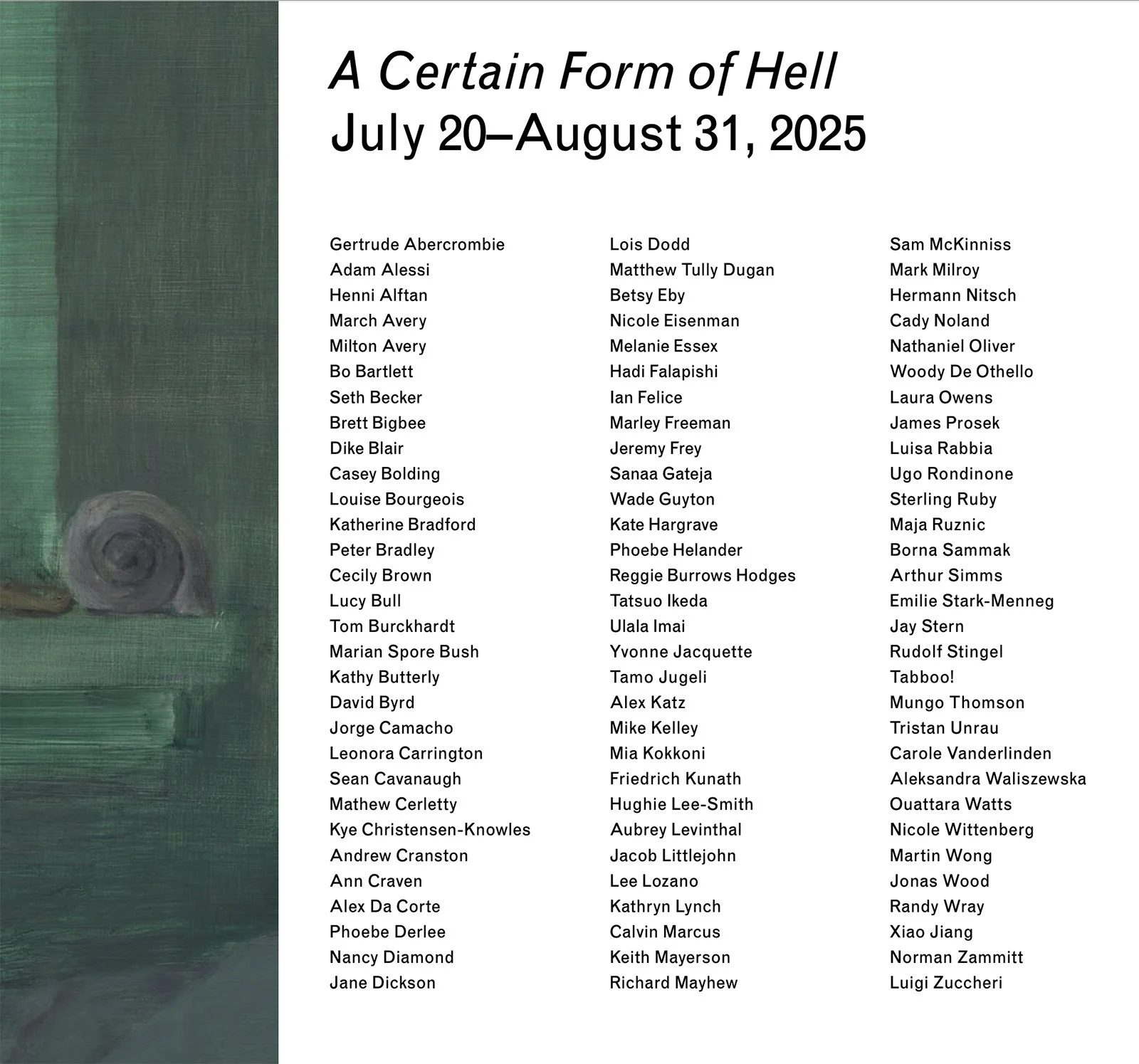

A Certain Form of Hell (2025)

As above, so below—every vision of heaven is mirrored by a depiction of hell. Paintings of the Last Judgment throughout the millenia, from Jan van Eyck to Michelangelo to William Blake to Buddhist Mandalas, set the two realms in relation, representing moral consequences as a dichotomous, mutually enabling pair. Inspired by Dante’s Inferno, the counterpart to the Italian poet’s Paradiso, artists like Sandro Botticelli and Gustave Doré have attempted to map hell’s nine circles, charting its strata from the Earth’s crust down into its core. Following A Particular Kind of Heaven, last year’s exhibition sited in Ann Craven’s deconsecrated church in Maine, Karma presents A Certain Form of Hell. Titled after a 1983 Ed Ruscha painting just like its predecessor, the exhibition features works exploring the netherworld in its many manifestations.

Warming, cleansing, life-giving—fire is also the archetypal symbol of hell. Milton Avery’s Charred Forest (1939) shows its ashy aftermath in the Canadian Gaspé Peninsula, where he spent a formative summer developing the luminous planes of color that would define his mature style. While Avery’s painting suggests both destruction and the promise of rebirth, Mungo Thomson’s Wildfire (June) (2021) shows the blaze still raging, its flames illuminated by an LED lightbox. The absence of light can also be hellish, as in the windows opening out onto a black void in Henni Alftan’s Darkness (2024) or the door to nowhere in Hughie Lee-Smith’s The End (The Pink Door) (1998). Cecily Brown’s Wee Hell (2025) also transcends fiery hues, instead taking cues from Old Master treatments of the underworld and translating them into a kaleidoscopic inferno of whirling brushstrokes.

Other artists draw our attention to the sinister underbellies of supposedly neutral objects and places, probing our cultural unconscious. Martin Wong’s Eye of Providence (1975) riffs on the design of the US dollar bill, highlighting the cleaved pyramid that some believe symbolizes malevolent secret societies—namely, the Illuminati. Mathew Cerletty’s photorealist, oil-on-linen Ribeye (2025) crops in on two glistening slabs of meat, industrially packaged and ready for consumption. Jane Dickson’s LV 82 Casino Girls Red Felt (2021), painted on a blood-red swath of the titular textile, depicts figures transfixed by the glow of slot machines, suspended in some self-inflicted purgatory. Leonora Carrington’s graphite drawings of Parisian street scenes find hell, as Jean-Paul Sartre famously quipped, in “other people.” Mike Kelly’s darkly humourous Length (1985) implies that the male psyche is an underworld all its own.

Hell can be abstract, as immaterial and wrenching as a feeling. Viennese Actionist Hermann Nitsch’s Rovereto VI 64.Malaktion (2012) is visceral, its ridges of scarlet paint manipulated with the artist’s fingers during one of his gory performances. Peter Bradley’s Nix Olympia (1973), its colors applied via spray gun, appears not bodily but mineral, like lava roiling out of the depths. The crimson ground of Richard Mayhew’s phosphorescent Untitled (Abstract Composition) (1975) is horizontally bisected by a blue current, the work reads as both landscape—perhaps the banks of the River Styx—and color field. Comprising nine perfect circles excised from silver cardboard, Cady Noland’s (Not Yet Titled) Parkett 46 (1996) conveys the violence of a stockade from geometry alone. While this form of torture is medieval, Noland’s evocation of the burning shame of public humiliation resonates in a contemporary culture intimately familiar with the spectacle of suffering. If, as Dante wrote, “the path to paradise begins in hell,” a consideration of the underworld is a necessary evil.

Gertrude Abercrombie, Adam Alessi, Henni Alftan, March Avery, Milton Avery, Bo Bartlett, Seth Becker, Brett Bigbee, Dike Blair, Casey Bolding, Louise Bourgeois, Katherine Bradford, Peter Bradley, Cecily Brown, Lucy Bull, Tom Burckhardt, Kathy Butterly, David Byrd, Jorge Camacho, Leonora Carrington, Sean Cavanaugh, Mathew Cerletty, Kye Christensen-Knowles, Andrew Cranston, Ann Craven, Alex Da Corte, Phoebe Derlee, Nancy Diamond, Jane Dickson, Lois Dodd, Matthew Tully Dugan, Betsy Eby, Nicole Eisenman, Melanie Essex, Hadi Falapishi, Ian Felice, Marley Freeman, Jeremy Frey, Sanaa Gateja, Wade Guyton, Kate Hargrave, Phoebe Helander, Reggie Burrows Hodges, Tatsuo Ikeda, Ulala Imai, Yvonne Jacquette, Tamo Jugeli, Alex Katz, Mike Kelley, Mia Kokkoni, Friedrich Kunath, Hughie Lee-Smith, Aubrey Levinthal, Jacob Littlejohn, Lee Lozano, Kathryn Lynch, Calvin Marcus, Keith Mayerson, Richard Mayhew, Sam McKinniss, Mark Milroy, Hermann Nitsch, Cady Noland, Nathaniel Oliver, Woody De Othello, Laura Owens, James Prosek, Luisa Rabbia, Ugo Rondinone, Sterling Ruby, Maja Ruznic, Borna Sammak, Arthur Simms, Marian Spore Bush, Emilie Stark-Menneg, Jay Stern, Rudolf Stingel, Tabboo!, Mungo Thomson, Tristan Unrau, Carole Vanderlinden, Aleksandra Waliszewska, Ouattara Watts, Nicole Wittenberg, Martin Wong, Jonas Wood, Randy Wray, Xiao Jiang, Norman Zammitt, Luigi Zuccheri.

July 21–September 1, 2024

Karma

A Particular Kind of Heaven

70 Main Street, Thomaston, Maine

Learn more

July 20–August 31, 2025

Karma

A Certain Form of Hell

70 Main Street, Thomaston, Maine

Learn more